In the last energy code update, some jurisdictions have introduced a new requirement colloquially referred to as the “envelope backstop.” What exactly is the envelope backstop, and why did policymakers introduce it? What are the implications of the envelope backstop for designers, and is it working as intended?

The energy codes in the United States establish requirements for major energy consuming systems in a building. The two most commonly adopted energy codes are the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) and ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1 (ASHRAE 90.1). These codes include several compliance paths depending on the building occupancy, size, and system types. This article focuses on larger, commercial buildings whose envelope systems are one of the key features of marketability to potential tenants or owners. Building envelopes are the public’s first introduction to a building and can allow occupants to feel more connected to the exterior environment through the use of highly glazed areas.

Photo courtesy of Getty Images; dmbaker.

"Though most builders think of polyiso as a product used in low-slope roofs, its excellent performance has expanded its market share in applications on roofs and walls of all kinds..."

Example buildings with highly glazed fenestration systems.

Designers sometimes employ highly glazed fenestration systems such as curtain wall, window wall, and storefront systems to, among other reasons, minimize a building envelope’s thickness and maximize leasable floor area. Additionally, some fenestration systems reduce the number of trades required to enclose a building relatively quickly, which is ideal for sites where access and construction schedule are significant project constraints. However, fenestration thermal performance has some practical limits due to the metal components necessary for structural support and, to a lesser extent, the large areas of glass. Designers therefore are often required to use an energy model to demonstrate energy code compliance because the prescriptive energy code requirements for building envelopes have become more stringent in recent code cycles.

For example, the prescriptive code path limits the amount of glazing for a commercial building to 30 percent of the vertical wall area (or 40 percent if implementing additional daylight responsive controls for lighting). An energy model can be used to offset lower performing envelope systems with the mechanical and lighting systems; this practice is referred to as “tradeoffs.” Generally, this strategy results in buildings with envelopes performing lower than prescriptive code, even if the overall building is code compliant. In an attempt to limit this tradeoff practice, in 2020, New York State (NYS) and Massachusetts (MA) policymakers, for example, introduced an additional calculation requirement when the energy model code compliance path is used. This additional calculation is referred to as the “envelope backstop.” In this article, we compare the NYS and MA envelope backstop calculations because the methods differ. We will also show how, in some cases, the calculations may have unintended implications that contradict policymaker goals to reduce building energy consumption.

Why Require an Envelope Backstop Calculation?

Policymakers continue to increase the stringency of prescriptive envelope requirements with each code cycle because they recognize the opportunity to passively reduce building energy consumption. Well-insulated, airtight envelopes with fewer thermal bridges and careful placement of glazing based on orientation and shading can reduce the loads on mechanical systems. Building envelopes play a major role in passively managing energy consumption and, once constructed, are typically not modified in any substantial way for thirty or more years. While some designers may view the more stringent prescriptive requirements as prohibitive to the design and development process, the code permits designers and building owners who desire to maintain a certain aesthetic to use the performance energy modeling path to achieve their goals. The policymakers’ goal for implementing an envelope backstop calculation is to improve building envelope system performance by placing limits on how far the building envelope systems can stray from the prescriptive requirements when using the performance modeling paths.

New York State Stretch Energy Code and Envelope Backstop Calculation

The NYS Stretch Energy Code has been adopted by New York City (NYC) and a few NYS counties1. The NYS Stretch Energy Code requires buildings 50,000 square-feet or greater that use an energy model for compliance to complete one of the following:

Comply with prescriptive building envelope requirements, or,

Perform a COMcheck analysis that demonstrates the overall envelope performance is not worse than the criteria noted in the table below, based on occupancy. If fenestration area is 40 percent or more of the gross above-grade wall area, the analysis must account for an additional solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) criterion.

COMcheck is a software tool developed by the Department of Energy to perform an envelope energy tradeoff calculation following the ASHRAE 90.1, Appendix C methodology. The software requires designers to input all envelope system surface areas and thermal performance information. COMcheck then outputs a percentage for the proposed design that is either better or worse than if the envelope was built to the prescriptive code requirements.

Occupancy | Maximum AllowableCOMcheck Result |

Multifamily, Hotel/Motel, and Dormitory | 15% worse than prescriptive code |

All Other | 7% worse than prescriptive code |

Mixed Use | Calculated from a gross wall area‑weighted average |

NYC worked with the DOE to incorporate the envelope backstop calculation directly into the COMcheck software to assist designers with documenting compliance and accounting for the additional SHGC criterion if the fenestration area exceeds 40 percent of gross above-grade wall area. For example, suppose COMcheck shows that a commercial office building envelope is 2 percent worse than the prescriptive code-compliant building envelope. In that case, the project complies with the envelope backstop calculation because the criterion permits the envelope to be up to 7 percent worse.

Massachusetts Energy Code and Envelope Backstop Calculation

MA has its own stretch energy code which is more widely adopted2, and it has chosen to use a different method for the envelope backstop calculation. In MA, the stretch energy code requires buildings over 100,000 square-feet and laboratories over 40,000 square-feet to demonstrate 10 percent better energy performance compared to the requirements established in ASHRAE 90.1 Appendix G Performance Rating Method on either a site or source energy basis. In addition, these projects must submit an envelope backstop calculation following an area-weighted calculation outlined in Section C402.1.5 of the 2018 IECC, referred to as the “Component Performance Alternative” calculation. This calculation provides an area-weighted tradeoff methodology for envelope system thermal performance using a simple spreadsheet approximation of heat transfer. The goal is to show heat transfer through the proposed envelope will be less than heat transfer through a “code minimum” envelope. The intention is to allow design flexibility while maintaining a limit on overall heat transfer.

The calculation accounts for the above-grade walls and roofs, the slab-on-grade perimeter condition, and the below-grade walls. For projects with vertical glazing area or skylight area that is greater than allowed by code, the calculation will account for this additional area; otherwise, it is excluded from the calculation. The maximum allowable vertical glazing area is 30 percent of the above‑ grade wall area with an option to use 40 percent if daylight responsive controls are implemented. For core-and-shell projects where it is difficult to demonstrate that the required daylight controls will be implemented, we suggest using the 30 percent maximum vertical glazing area and 3 percent maximum skylight area as the code-allowed areas within the calculation to avoid potential permitting issues.

Envelope Backstop Calculation (Case Study)

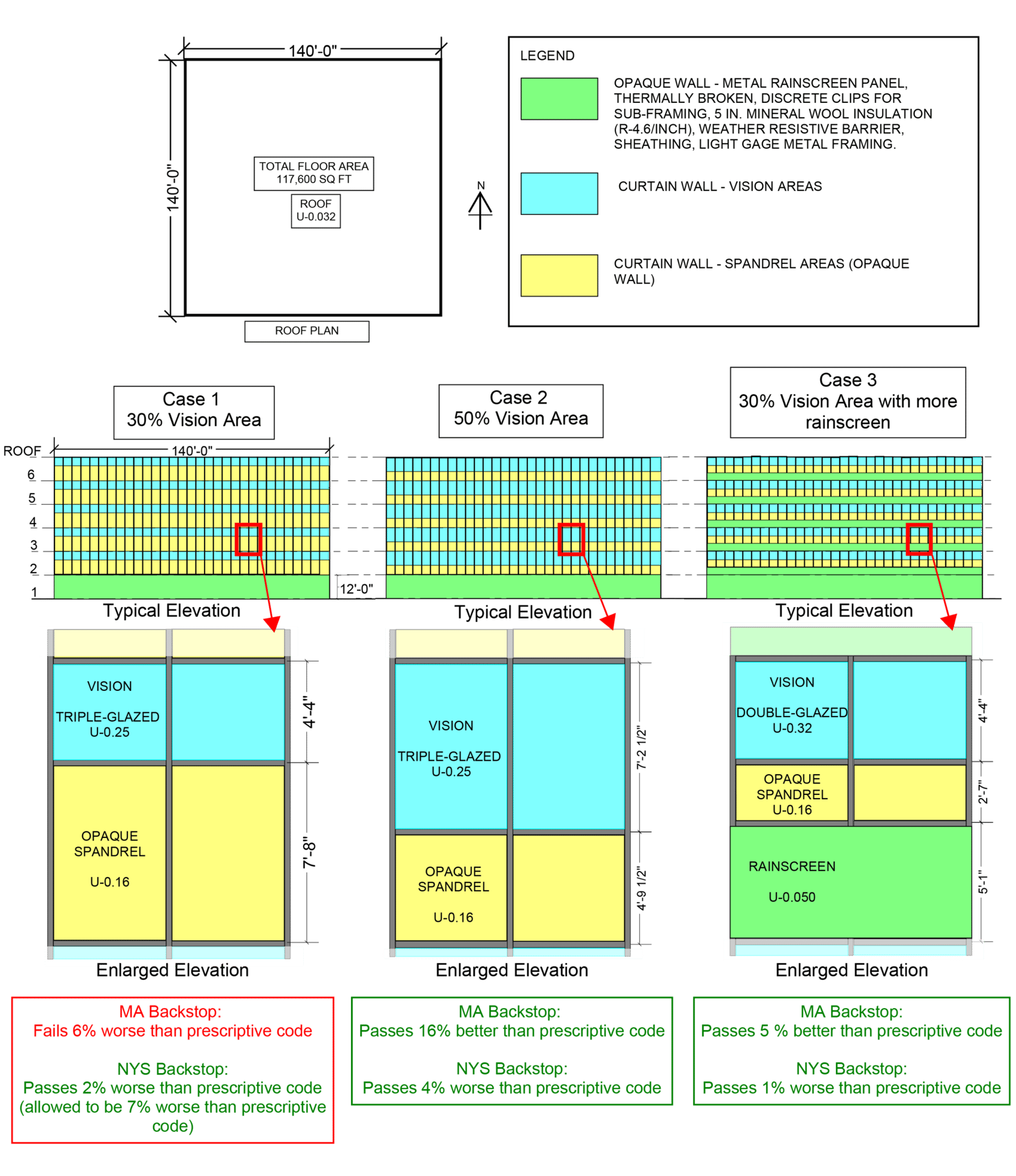

To better understand some of the implications of these calculation methods, we performed the NYS Stretch Energy Code backstop calculation (COMcheck) and the MA backstop calculation (Component Performance Alternative) on three variations of an example 6-story building. The building envelope systems include opaque rainscreen-clad walls at the ground level and curtain wall with vision and spandrels (opaque areas of curtain wall) at the upper levels. We varied the proportions of these three envelope systems as shown in Figure 2 below. The COMcheck and Component Performance Alternative backstop calculation results are summarized below.

Figure 2 – Example building.

Our results show that using the MA method, Case 1 with triple-glazing and prescriptive 30 percent fenestration area fails to comply, whereas increasing the vision glazing area to 50 percent and reducing the spandrel area in Case 2 complies with the backstop calculation. Similarly, using a lower‑performing double-glazed system and installing more rainscreen wall instead of spandrel complies with the backstop calculation. The reason for this becomes evident when reviewing the prescriptive requirements for each envelope component type. Specifically, curtain wall spandrels are classified in the energy code as opaque systems and must be compared against a baseline prescriptive requirement for an opaque wall of U-0.064, whereas the vision areas are classified in the energy code as fenestration and are compared against U-0.38. The U-factor is a metric for how thermally conductive the assembly is; the higher the U-factor, the more heat transfer occurs, indicating that the system has lower thermal performance.

For vision areas of curtain wall systems, there are many options for glazing with high thermal performance and thermally broken frames with overall U-factors that are better than the prescriptive code requirement; however, it is currently not possible to achieve the prescriptive code requirement of U-0.064 maximum for curtain wall spandrels because the spandrel insulation is interrupted by the curtain wall frames (We assume that interior-applied insulation is not an option due to condensation risk). For these reasons, the higher glazing surface area can offset the lower-performing spandrels in the backstop calculation; however, in reality a spandrel performs thermally better than the glazing as demonstrated by comparing their U-factors (i.e., Uspandrel-0.16 is less than Uglazing-0.25). The reason why the U-factor for spandrel is lower than glazing is because insulation can be installed inboard of the spandrel glass to reduce heat transfer through the assembly.

The NYS Stretch backstop uses COMcheck, which employs a simplified energy balance calculation instead of an area-weighted calculation; all three cases pass because less than 7 percent worse than the prescriptive code. The NYS Stretch Code criteria for an office building notes that the envelope is permitted to be up to 7 percent worse than prescriptive code. Case 2 is slightly worse than Case 1, which makes sense based on the actual U-factors and areas for the envelope components. Case 3 is also shown to be the best, which makes sense because it has the largest opaque rainscreen area. The opaque rainscreen system is the best performing system out of the three system types.

Our simplified case study comparison indicates that the COMcheck method employed by NYS is more representative of actual thermal envelope performance than the MA method.

Conclusions

The envelope backstop calculation was introduced by policymakers to limit how far building enclosure thermal performance can stray from the envelope prescriptive requirements when using an energy model to demonstrate code compliance. MA and NYS introduced different calculation methods. MA uses the Component Performance Alternative calculation in IECC (area-weighted average calculation) and NYS uses ASHRAE 90.1, Appendix C (COMcheck calculation). Our three variations on a simplified case study example comparing these two methods shows that the COMcheck calculation is more representative of actual performance, and the MA calculation can have the opposite effect, especially for buildings with curtain wall spandrel areas—encouraging more highly glazed envelopes—which appears to be counter to the policymakers’ goal.

Based on our recent experience completing envelope backstop calculations for several projects, we recommend designers consider the following during the design phase:

- Perform the envelope backstop calculation as early as possible during design phase. This step will inform designers on significant design decisions that could impact aesthetic, cost, and construction scheduling and sequencing. These decisions include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Establishing the appropriate percentage of vision area, spandrel, and rainscreen wall areas.

- Determining if increased opaque cladding and/or roofing insulation will be required.

- Determine if higher-performance fenestration and glazing assemblies will be required (i.e., will triple-glazing be required?).

- Confirm that the proposed U-factors used in the envelope backstop calculation are representative of the actual thermal performance of the intended building enclosure systems that are available on the market. For instance, once the curtain wall U-factors are obtained from the curtain wall fabricator, use these values to re-run the backstop calculation to verify compliance.

- Be cautious with spandrel thermal performance assumptions. If miscalculated, this can have significant impact on the envelope backstop calculation.